|

AUTHOR INTERVIEW:

Barbara Quick

Author of A GOLDEN WEB

(YA Historical Fiction)

|

|

Barbara Quick's Blog

|

Barbara Quick's

Website

|

|

Alessandra Giliani

Italian anatomist, serving as the first woman

prosector, or preparer of dissections for anatomical study

|

A tower in San

Giovanni in Persiceto, Alessandra Giliani's birthplace

|

Bologna is

characterized by portici or covered walkways

|

Bologna

University

late 14th century

(Laurentius de Voltolina)

|

|

At the Archiginnasio,

one of the magnificent public libraries in Bologna

|

|

|

Barbara Quick

at the top of the Asinelli Tower, high above Bologna

|

Click bookcover for book trailer for VIVALDI'S VIRGINS

|

Dante

|

Abelard and Heloise |

|

BOOK

ILLUMINATIONS

|

|

|

Interview:

HISTORICAL FICTION AUTHOR BARBARA QUICK

Barbara Quick

|

A Golden Web

|

Author Biography:

Award-winning

novelist Barbara Quick learned Italian to do the research for her two

historical novels set in Italy, Vivaldi's Virgins (published in 2007: now translated

into 14 languages) and A Golden Web.

An avid traveler, she spent two different field seasons in arctic

Alaska to research her first novel, the Discover Prize–winning Northern Edge (HarperCollins 1990). She has written

for the New York Times Book

Review, Ms. magazine, the Los Angeles Times, San Francisco

Chronicle, and Newsweek.

Barbara Quick

started her writing life in Southern California, where

she frequently cut school to write poetry and cultivate an organic

vegetable garden. A graduate of the University of California at Santa

Cruz, majoring in English and French, she worked on her pre-first novel

while living in a tower cottage in rural County Cork, Ireland.

Barbara can speak, with varying degrees of proficiency, French,

Italian, German, Brazilian Portuguese, Spanish, and a little

Hungarian. This year, Barbara began studying the viola. Her

motto is, "Better late than never!" Because she loves

flowers and having bouquets around the house, she

tries to keep a picking garden in bloom for as much of the year as

possible. Cooking is also a major enthusiasm. Barbara

specializes in Northern Italian and Southern French cuisine, with an

emphasis on improvisation.

Merri: Barbara, thank you for taking the time

to answer a few questions for readers. I read and loved VIVALDI'S

VIRGINS. I was particularly struck by the poetic use of language

in that novel. As a medieval enthusiast, I secretly hoped you

would choose the Middle Ages as a time period for a novel. I was

thrilled when I discovered that A GOLDEN WEB took place in Medieval

Italy! When I read A GOLDEN WEB, I was struck by how well you

integrated the time period into your novel while still writing a novel

to speak to modern readers. Without further ado, let's begin.

What inspired you to write A GOLDEN WEB?

Barbara Quick:

My last novel gave me the

opportunity to tell the world about a brilliant and talented young

woman who had been, up until the publication of my book, a mere

footnote in obscure musical histories. Researching and writing

VIVALDI'S VIRGINS was such a satisfying experience. Sharing the story

with wonderful readers like you, Merri, has made all the uncertainties

associated with being a writer seem altogether worthwhile--especially

now that the novel has been translated into 14 languages.

When

the book was out of my hands, in production at HarperCollins, I found

myself asking, how many other such 'lost girls' are there, stranded in

the shoals of history and waiting to be rediscovered? I realized that

there must be hundreds--even thousands of them.

I suddenly felt that perhaps I could find and rescue some more of

these lost girls: that I could be a sort of tug-boat that gets them out

into open water, where they can raise their sails and catch the wind.

History has a tradition of

forgetting the brilliant and talented females who lived and worked

contemporaneously with the men whose lives have been so lovingly and

painstakingly chronicled by historians. Really intelligent people have

been all too willing to believe that creative brilliance was, somehow,

the exclusive province of men.

There are even some people today who persist in this belief, almost

as a kind of habit. We look through an encyclopedia and think nothing

of it that there are almost no women there on the pages!

This

gap--this injustice--is what inspired me to plunge into the past again,

to reach my hands out in the darkness, and see who grabbed hold of me.

This time, it was Alessandra Giliani.

Merri:

How did you

discover references to this real historical woman and what made you see

her story needed to be told?

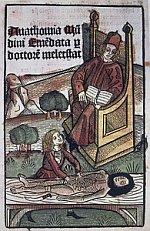

Barbara Quick: There's controversy, in the circle

of academics who study the history of medicine, about whether

Alessandra Giliani actually lived. Was there a real girl, born in the

early 14th century in Persiceto, who made a major anatomical discovery

while working for Mondino de' Liuzzi?

One article I found in Italy suggested that a chronicler working

for wealthy patrons in the 18th century made up Alessandra's story as a

way to flatter the locals in the place where she is said to have been

born and raised, San Giovanni in Persiceto.

The author of the article suggested that this chronicler "borrowed"

the story of an 18th century female anatomist who lived in Bologna

(even though the story of that anatomist is quite different from

Alessandra's story). He poo-pooed the idea that manuscript

illuminations depict Alessandra, or any girl, assisting Mondino. Men

wore their hair long back then, he insisted.

But those illuminations show not just the hair but also the face

and body of a young female working as Mondino de' Liuzzi's

prosector--at least it seems so to me!

I wasn't able to find any

reference to Alessandra in the 14th century archives I consulted. But

the head librarian in Persiceto, a distinguished scholar herself, told

me that what Alessandra did was such an affront to the social mores of

the time that all records of her--and even her family--could have well

been destroyed by the Church.

To me, this mystery makes the story

even more intriguing.

While

I was doing my research and writing the novel, I never for a moment

thought that Alessandra might be anything other than a real girl. She

felt real in the same way that Anna Maria dal Violin seemed utterly

real to me while I was writing VIVALDI'S VIRGINS.

In both cases,

I learned as much as I could about the history and

culture surrounding their lives. These historical facts provided the

settings for both novels, and dictated both their limits and

possibilities--it's important to me to be historically accurate.

But the stories

themselves--the characters and their interactions,

the words they spoke and the hopes they harbored--all of that came from

another place, a dark, mysterious place, which is both inside and

outside me, in the realm of what I guess is usually called the

collective unconscious.

There

was a mystical component to writing this novel, in that the story

seemed to write itself: it was as if I were remembering the story

rather than creating it. I heard the characters speaking. I felt

Alessandra's spirit. I felt her desire to be known and remembered.

Maybe

in feeling what I felt about Alessandra, I was feeling something that

is true--and has been true throughout history--for all the girls and

women in the world whose work and thoughts, ambitions and passions have

been deemed to have no lasting value.

Merri: How did you

research your characters?

Barbara Quick: I went to Bologna to begin my

research while my book contract was still being drafted at

HarperCollins. I spent three weeks there--and one of the most startling

discoveries I made, right off the bat, was how very long ago the 1300s

were! Mostly, they've been all covered up by subsequent eras of

history. The architecture is mostly gone, even in the historical center

of Bologna, covered up by the Renaissance and Baroque periods. I had to

go underground--literally, in crypts and sewers--to look at whatever

traces of the 14th century are still extant.

Merri: What discoveries did you

make? How did the research affect you?

Barbara Quick: I

felt like I was on a solitary

treasure hunt, the entire time I was in Bologna. I walked for hours and

hours every day on those cobbled streets and even along a pilgrimage

road. When I had too many blisters to walk any more, I borrowed a

bicycle from the sweet little hotel where I stayed--the Hotel Porta San

Mamolo--and rode it everywhere, without a helmet, I'm afraid. Greater

Bologna is an intensely urban environment, with buses and motorcycles,

where, back home, I never would have thought about riding a bike. But I

was on a mission--and I had blisters! When I wasn't searching for some

archive, plaque, or painting, I was in the pharmacies, looking for a

better blister remedy!

The

people who owned the hotel were so sweet to me! I'd return to my room

exhausted after a long day of research in various archives and museums

from one end of the town to the other. There would be a knock at the

door--and there was a little boy, sent up by the concierge with a tray

of tea and biscuits for me, and a vase of flowers from the hotel's

garden. Roberto Condello, the owner of the hotel, would proudly

introduce me to other guests as "Barbara Quick, our American writer."

Bologna

was a far cry from Venice, where I really didn't make any friends, even

though the director of the Vivaldi Institute was very nice to me. In

Bologna I was befriended by several people who were unbelievably kind

and helpful. It's a much friendlier city, in general, than Venice,

where the locals have been pretty jaded by all the tourism, for

hundreds of years.

For whatever reason, there isn't that much tourism in Bologna--even

though the food there is spectacularly delicious, and the historical

city center has a great deal of charm. I would go back in a heartbeat!

Merri:

Alessandra

Giliani

lived in Medieval times, times quite different from our own and yet

times when individuals faced similar challenges. What

similarities do

you see facing young adults today?

Barbara Quick: As the mother of a teenager, I can

say with some authority that hormones are hormones--and being a

teenager (or the parent of a teenager!) is a difficult thing, in any

century. Parents have certain expectations--and young people have their

own ideas (and are convinced--as I was, when I was that age--that their

ideas are far more brilliant and original than those of their elders).

I

was struck by the similarities between the advent of our own

Information Age, brought into being by the Internet, and the sudden,

radical need for books that was brought about by the advent of Europe's

first universities--among them, the University of Bologna. Books were

rare, precious things before that time. Unless you were very rich, if

you wanted to learn something, you had to memorize it! People were much

better at memorizing back then than we are...

The printing

press had not yet been invented. But all these students and their

professors needed books!

The

University of Bologna in the early 1300s was quite a radical place,

even more radical than UC Berkeley in the 1960s. It was run by the

students, who hired and fired their professors and made a lot of the

rules--and rebelled when they didn't like the rules.

It

wasn't at all that much of a stretch to imagine Alessandra's

predicament, wanting to be part of this radical world--and yet being

banned from it, by virtue of her gender.

There

are so many things that are equally unreasonable in our own time.

Society has such confused--and confusing--attitudes about girls and

sexuality, for instance. Look at the magazine ads, and the way young

girls are depicted there, and you get one message. But then listen to

what parents and teachers and psychologists are saying, and you get a

very different message indeed!

Alessandra

had the same problem: she knew certain truths about herself--but

society refused to acknowledge them. She was brilliant and wanted to

study. Society had its own ideas. Like the French say, "Plus ca change,

plus ca ne change pas!"

Merri:

How does her story

speak to adult readers?

Barbara Quick: I didn't dumb anything down when I

wrote A GOLDEN WEB, even though I knew it was to be published as a

young adult novel. Really, I wrote just the sort of novel I like to

read. Well, I always try to do that--because I don't think it's honest,

artistically, to try to write for a particular audience. In the final

rewrite, my editor, Rosemary Brosnan, encouraged me to put in a bit

more romance for Alessandra--which I happily did. I wanted her life to

be just as full and exciting and satisfying as possible, considering

the historical circumstances.

As

I know you know, as a Medieval expert, people lived very intensely back

then. Their lives were much shorter, in general, than ours--but they

lived them very fully, with great gusto and passion (especially in

Italy!). They laughed and cried and loved with a grandeur and honesty

that I think modern readers, whether adults or teenagers, can only

admire.

The world was completely alive for them, too. Angels and demons

were real for them, found everywhere. Magic and miracles were part of

everyone's reality--respected, hoped for, and feared. Maybe it's those

rich primary colors one sees in the illuminated manuscripts of the

time--but I can't help feeling that the air was somehow clearer and the

world was more brilliant and gorgeous than the world we live in today.

Merri: How does

historical fiction speak to readers as compared to history?

Barbara Quick: Well, that's an easy one. History

is, for most people, rather difficult to read. Historical fiction, if

it's done well, is simply a pleasure. Instead of learning a lot of dry

facts and dates, you get plunked down into a fully imagined world,

where you learn by simply looking around you and listening and becoming

involved in the lives and thoughts of people who seem completely real.

It's the nearest thing we have to time travel (both for readers and

writers!).

Merri: Barbara, I felt like I had been

transported right into Medieval

Italy when I read Alessandra's story. I too enjoy

historical fiction because it brings a period and especially the people

alive. Thank you for agreeing to the internview and sharing with

with your readers.

Interview:

Copyright Barbara Quick and Book Illuminations, Jan. 2010.

All rights reserved.

Book clubs,

libraries and other reading groups are free to use this

interview as a supplement free of charge. Book Illuminations

would appreciate credit through use of a source citation.

|

|

|